Beyond the Pink Curtain: How South Asia Styles, Sells, and Subverts Women's Political Power

- CGAP South Asia

- Jun 24, 2025

- 5 min read

Introduction: A Colourful Illusion?

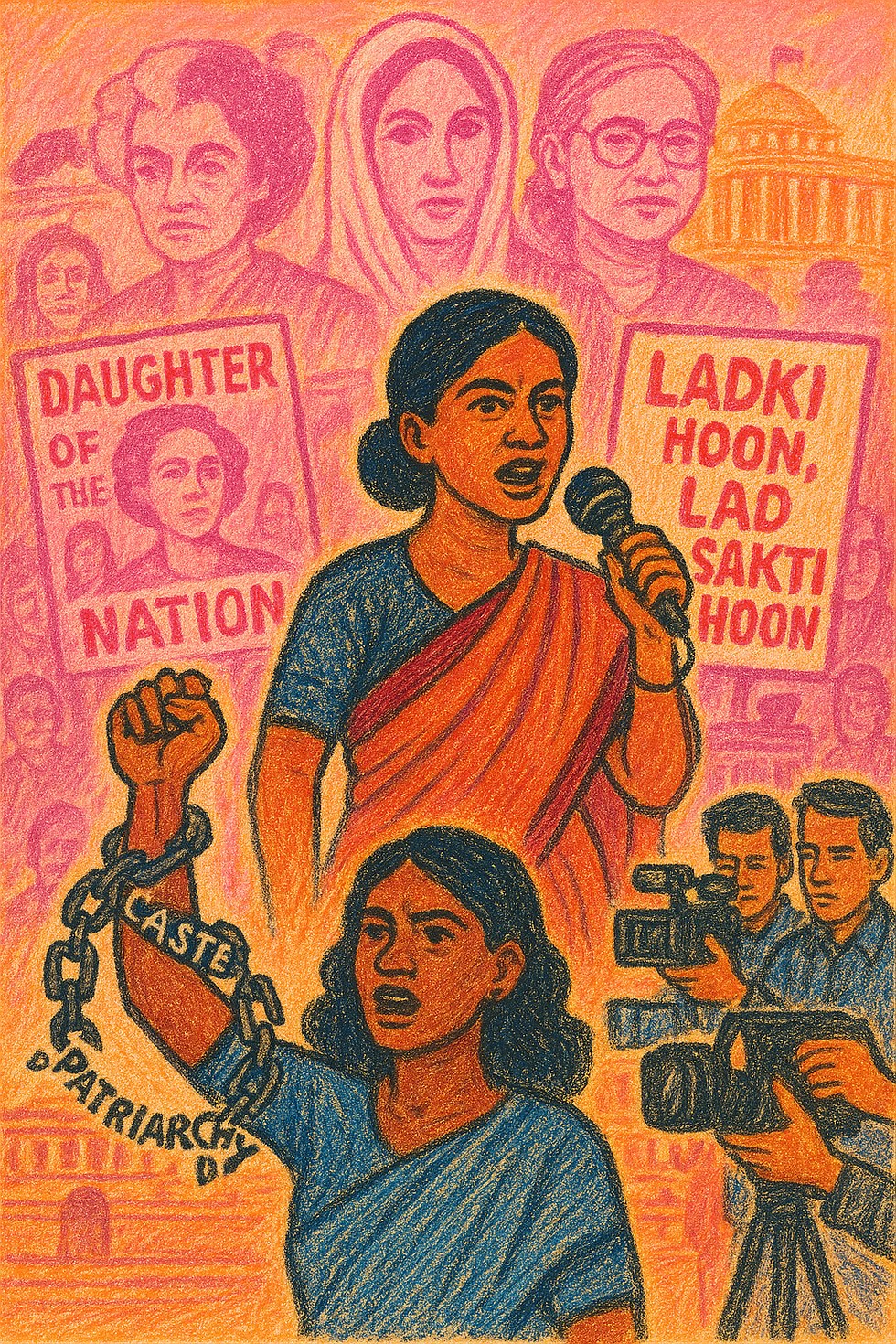

In the grand theatre of South Asian politics, where symbolism often overshadows substance, women’s political participation remains wrapped in layers of emotional performance and aesthetic design. Women’s representation in politics is packaged within strategic aesthetics; emotional narratives of motherhood, sacrifice, and campaign posters all contribute to a branded women’s representation in politics that distributes aesthetic meaning. This is more than branding; it is what is often casually termed in political and feminist discourse, increasingly “Pink Politics,” a curated image of progress appears progressive to an extent but ultimately reproduces the very limitations of traditional gender roles.

Unpacking Pink Politics: Aesthetic or Agency?

Pink Politics extends beyond colours and campaign iconography. It consists of a strategic framework with elements of emotional and gendered symbolism that soften the realities of a woman’s presence within hierarchical political spaces and party elites. Female politicians are often framed as mothers, daughters, and widows, roles that invoke emotional connection but strip them of political agency. This creates a "masquerade of equality," the illusion of inclusion that conceals the reality of exclusion (Robinson 2018; Saeed et al. 2023). It is a space for women to be seen, but always in limited agency in controlled forms that exclude anyone not in their party elite, or dynastic groups, or fit norms informed by patriarchal genealogies and caste hierarchies in South Asia. While women may operate in roles that clearly draw on emotive or familial frameworks outside of these patriarchal forms of sociality, left to their own devices, a female leader’s legitimacy is often predicated on her availing herself of these tropes.

Gendered Campaigns Across Borders: The Regional Picture

Across the region, women are seen more as heirs to legacies or emotional figures than as architects of governance. Despite the towering legacies of figures like Indira Gandhi or Benazir Bhutto, South Asia continues to narrate women’s political journeys through limiting gendered lenses. Emotional narrative trumps administrative credibility.

Mamata Banerjee, a heavyweight in her own right, was recast in 2021 as "Bangla Nijer Meyekei Chaye (Bengal of daughter)" - a slogan that appeals to emotional connection, but ultimately overshadowed her administrative leverage. Similarly, Priyanka Gandhi's "Ladki Hoon, Lad Sakti Hoon" campaign elevates individual fortitude in place of visions for policy. In many cases, the respective political capital women possess is rarely identified as independent political capital but rather as an extension of familial legacy. Pakistan's Maryam Nawaz Sharif's conceptualisation of herself politically remains limited by her father's legacy, while Punjab's Bhandari remains politically understood through her late Marxist husband. Even Chandrika Kumaratunga's politics were legitimised as the leader of Sri Lanka in relation to her father's martyrdom and her mother's political legacy.

Women across South Asia collectively are constructed more as inheritors of generations' histories, or just maternal or domestic beings to create pathos, than as generators of political legitimacy. Moreover, it deepens the weighing of sacrifice over legitimacy or affective governance. Regardless of national contexts, there is a thin ideological and vaguely formed strategic link: women in politics can only normatively be permissible when they occupy and are associated with society's accepted family or moral constructs.

Media as the Mirror and Megaphone

Mainstream and digital media further exacerbate this framing so much so that it shifts focus to performative femininity campaigns. Hina Rabbani Khar was covered as Pakistan's Foreign Minister, but the majority of reports were focused on her wardrobe rather than her foreign policy. Sushma Swaraj textbooks' response to a range of international crises was hailed for her "motherly conduct" rather than her political strategy.

The online space is even worse. Amnesty's 2020 report on online abuse of women politicians in India documented the sexist, communal, and violent commentary bodies. UN Women in 2023 confirmed that the media in South Asia still frames women in limiting representations, more as symbols than as public representatives who exercise governance. This performative femininity undermines substantive engagement and aligns with making it clear that women must be clear about either an acceptable identity or conformity and descent into systemic sidelined and discredited.

The Intersectional Struggle: Margins within the Margins

Women from marginalized groups—Dalit, Muslim, tribal, or other minorities experience additional layers of barriers that can be even more insidious. Kimberlé Crenshaw's theory of intersectionality (2016) addresses the multidimensionality of the corruption of identities and diversities in the discrimination women face. For women such as these, participation in politics comes with layered risks. It is important to remember also that South Asian women who belong to these minorities will be viciously stereotyped and questioned as being legitimate in a movement.

Despite the above, many resist. They form coalitions, navigate exclusion, and begin to amend political spaces. Ultimately, their stories are predominantly neglected by mainstream narratives.

Breaking the Mold: Women Beyond the Frame

From within these spaces, women have incrementally and mostly quietly rewritten the rules of political action. Examples like Mariya Ahmed Didi representing the Maldives and former Human Rights Minister of Pakistan, Shireen Mazari, have taken unique but equally radical approaches to embedding gender equity as part of the legislative framework and human rights reforms. In Nepal, Rohini Acharya (the report’s author) is forming a homogenous federal governance that institutionalises constitutional safeguards for women's reservation, a vital component of our gender equality centre. These women are not just images. They are a movement and are appealing for a shift from symbolic inclusion to participatory power from within, that challenges the performative model.

What defines these leaders is not their alignment with traditional gender roles but their ability to transform governance structures, broaden representation, and challenge entrenched hierarchies. These women are transforming symbolic presence into participative presence - an important leap into exercising agency.

Beyond Pink: Reimagining Leadership Futures

To transform women’s political visibility in South Asia into meaningful leadership, there must be a shift from symbolic celebration to substantive engagement. Campaigns that emphasize womanhood and emotion, such as the “pink” movements, have played a role in creating visibility, but visibility alone is not enough. The discourse now needs to focus on self-determination, policy impact, and governance capabilities rather than defining women leaders by familial ties or moral virtues. The media must also move their focus from measuring and assessing women's physical appearance to assessing women's views, vision, and legislative priorities.

To undertake this transformation, it is necessary to orient to intersectionality, centering women from diverse and marginalized communities as political agents who have value, not token representation. Real change will only come through sustained investment in political education, grassroots leadership development, and systemic support, from the panchayat to the parliament. South Asian politics must reorient from the uncritical, pink-washed, token womanhood, to empowerment as women lead communities as policymakers, not as representation or inside politics as heirs. Inclusion means valuing the capabilities women bring, and prioritising their roles as governance leaders, moving from mere tokenism to transformative, systemic leadership.

About the author:

Rakshita

Rakshita is a researcher and advocate dedicated to gender justice and social equity. Her work focuses on amplifying the voices of marginalized communities, particularly sex workers and their collectives, through research, advocacy, and program implementation. Deeply drawn to partition history, she explores its lasting impact on identity, displacement, and social structures as a key research interest. With an MA in Women’s Studies from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, she strives to bridge policy and grassroots realities, creating inclusive and sustainable impact.

This article gives the views of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the position of Women for Politics.

Comments