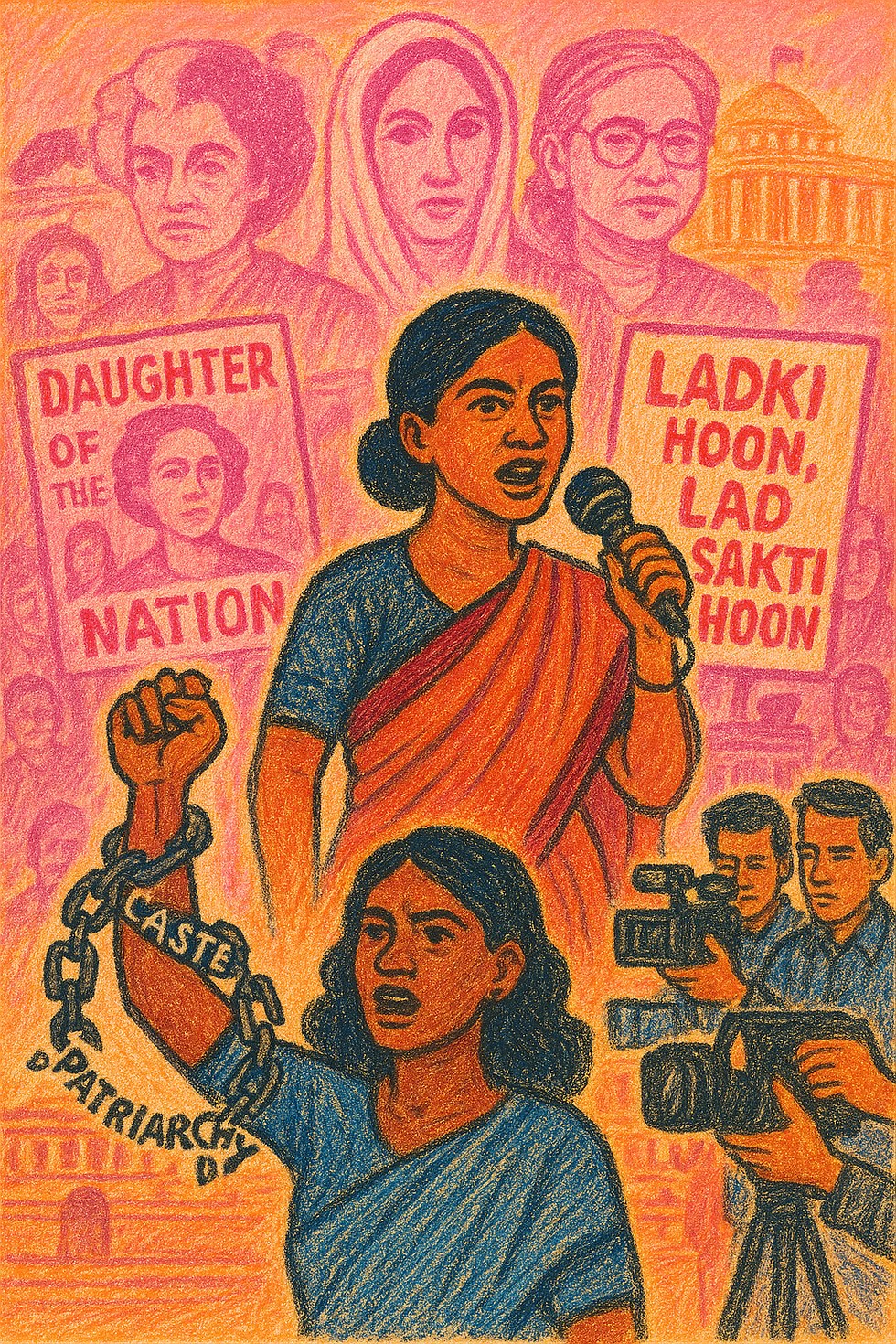

Breaking Bariers and Redefining Leadership: Women as Decision Makers

- CGAP South Asia

- Dec 27, 2024

- 4 min read

Dr. Harini Amarusuriya’s recent appointment as the Sri Lankan Prime Minister has been a landmark achievement. In an interview she gave right after becoming an MP, she said, “It's challenging for women leaders to actually take a stance and remain a part of their party. This is also one of the reasons why we actually need more women in politics. Increasing numbers would help us balance power within the parties, which may also shift towards the right. That will again be good because their men colleagues will not still dominate the women leaders in those parties.” Her statement underscores a critical truth: the underrepresentation of women in politics isn’t merely a numbers game—it’s about redistributing power by breaking down barriers, and changing the dynamics of leadership within political systems.

Systemic barriers limiting women’s participation in politics

Despite increasing awareness, women remain vastly underrepresented in leadership roles across politics, business, and other sectors. As per UN Women, of all women politicians globally, 87% held the Women and Gender Equality portfolio while 67% held Family and Children Affairs. When women leaders are pigeonholed into such roles, their voices in critical domains like finance, defense, or foreign policy remain underrepresented. Center for Gender and Politics (CGAP) conceptualised the Worth Asking interview series to challenge this very narrative. Instead of being plain old sawal jawab, Worth Asking interviews are crafted carefully to bring out the leadership that the politicians have demonstrated. CGAP interviewed politicians from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Maldives and found two commonly recurring themes.

1. Supportive private networks play a foundational role in encouraging the ambitions of women politicians. For instance, Dr. Anara Naeem of Maldives pursued higher education abroad with her brother’s support, while Fauzia Khan emphasized the role of her husband and his family in her political career. Nafisah Shah and Manisha Chakraborty spoke about their supportive parents who imbibed them with the confidence it takes to enter the political arena. However, while private support is necessary, it is not sufficient. Patriarchal public structures—such as unequal access to resources and networks—continue to hinder women’s participation at higher levels of decision-making, best summarized by Dorji Wangmo:

“As a young girl, growing up, I did not really feel any differentiation between boys and girls, per se, girls were allowed to and they could do whatever boys did…Even after I completed my studies and joined the workforce, I did not feel any difference. But as I progressed in my career, I did start to notice that the number of women climbing up the career ladder were declining as compared to men.”

2. Politics is a heavily hierarchical field, which means the support of mentors is crucial. For women entering this field, there is a lack of both role models and mentors. Moreover, since leadership is often associated with traditionally masculine traits such as assertiveness and dominance, women leaders face a "double bind." Being assertive leads to criticism for not conforming to gender norms, while being collaborative is perceived as weak. In the absence of clear guidelines, witnessing actual leaders navigating the political space is the best way to learn and become motivated to enter the field. Many leaders interviewed by CGAP pointed to role models who shaped their ambitions. Pakistani politician Nafisa Shah credited Benazir Bhutto as a significant influence, while Bangladeshi leader Manisha Chakraborty drew inspiration from Rani Bhattacharjee, an active leader in Bangladesh’s language movement.

Corrective measures

There was near-universal acceptance among the leaders interviewed for Worth Asking that reservation is a necessary corrective to centuries of gender imbalance. The Women's Reservation Bill in India, which proposes reserving 33% of seats in Parliament and state assemblies for women, has been a contentious issue for over a decade. While recently passed into law, its implementation is delayed until after 2026. Jothimani, a Congress MP, fiercely advocates for reservations, saying, “Women in public life…are generally judged by gender. This is a default in any political party, public space, or political system. Women are judged not on their talent or merit, but on their gender.” Nafisa Shah, herself elected to a reserved seat, played a crucial role in setting up the Women’s Parliamentary Caucus. She explains that it was an attempt for women parliamentarians to create space for themselves in a traditionally male space. In their meetings, the women developed a collective consciousness realising that even though they may come from different parties, there were similarities in their political career. She explains, “as we have these reserve seats, it is easy for men to push women back and put us on the back benches…that is something that we will…not want so [we became a space for] active, meaningful voices for women who often spoke for each other across the aisle as well.” Reservation remains a critical tool to address the historical underrepresentation of women in governance. It offers women the opportunity to contest and hold positions of power, but it also requires constant advocacy to ensure that these positions translate into meaningful political influence.

Despite the advantages of reservation, the issue is multifaceted. As Sobita Gautam highlights, women from privileged backgrounds may find it easier to navigate the political system, whereas grassroots women face significant socio-economic and cultural barriers. This underscores the need for intersectional measures alongside reservations to ensure equal opportunities for all women, irrespective of their class, caste, or socio-economic status. A reservation system alone will not dismantle the entrenched patriarchal norms, but it is an essential starting point to level the playing field.

The path to gender parity in political leadership is not straightforward. While supportive networks, role models, and corrective measures such as reservation have paved the way for women’s political participation, the real work lies in addressing the systemic barriers that persist. As the stories spotlighted through Worth Asking demonstrate, when women are empowered to participate in decision-making, they bring a diversity of perspectives that enrich policy discourse and strengthen democratic institutions. To truly transform political systems, we must continue to fight for policies that address both the overt and covert barriers women face, creating a future where leadership is defined by vision and competence, rather than gender.

Ragini Puri

Ragini is the Associate, Project Management at Centre for Gender and Politics. She has a background in journalism, with experience across both written and audio formats. Passionate about advancing gender equality, she is currently engaged in research on the Care Economy. Ragini holds an MSc in Empires, Colonialism, and Globalisation from LSE, equipping her with a multidisciplinary perspective on social and economic issues.

Comments